The COVID-19 pandemic has presented all of us with many challenges to navigate. Some people have had more time than ever and invested this into building sustainable habits for health and fitness.

However, for others (sometimes for reasons beyond their control), the past 18 months or so have led to extended periods of inactivity.

As opportunities increase for a return to pre-pandemic activities, this article will consider how best to approach this for yourself, or your mum or your dad. Keep in mind the process I am about to cover can be applied to almost anything.

Start with the end in mind

Defining your endpoint is the best place to start. In this instance, we will consider activities that might have happened pre-pandemic but have been shelved since COVID-19 hit. Different people will have different endpoints, and that’s absolutely fine.

We need to define this first as it guides where we start and the timeline for our plan. An example might be, ‘Return to visiting my daughter’s Sally’s place for dinner every Sunday’.

Determine what’s needed to succeed

Using the example above, we now have an endpoint. Next, we need to understand what is involved in this activity.

- Where does Sally live? Will getting to Sally’s place involve navigating steps? Getting in/out of a car? Walking on a footpath? If so, how far do we need to walk?

- When we get to Sally’s place, what are the chairs like compared with those at home? Are they higher or lower? Are they easy to get up and down from? (The same applies to the toilet.)

- In some cases, we may even need to consider the meal. I know from my own experience that my father-in-law has mainly had microwave meals for the past 18 months that are soft and can be eaten with a fork. As a result, he’s lost some dexterity and strength, which has made cutting meat tricky.

Establish the baseline

We’re starting to build a good idea of what we are trying to achieve.

We now need to consider the ‘fitness gap’, or the difference between where we are now and where we need to get to.

Physiotherapists have literature-based tests they can use, but it doesn’t need to be that complicated. Specificity is key. If you know what you need to do to succeed (see above), you can test yourself against this.

For example, if you need to walk 30 metres down Sally’s hallway, have a go at walking 30 metres. If you can only get to 10 metres, we know there is a 20 metre gap.

This tells us we need to develop walking endurance. At the same time, we might find things we can ignore. If the dining chairs at Sally’s are the same as those at home, and there is no problem getting up and down from them, the fitness gap for this task is zero.

Plan and execute

With the information above, we now have a framework for building our plan.

You have two options here: spend time educating yourself about basic exercise principles; or work with a professional who can help you avoid the pitfalls.

Your own experience and knowledge will likely determine the path you choose. Working with a professional is an investment, but this guidance can work wonders in the long run and save a lot of time, stress and money.

I have worked with many people who have avoided professional help, only to end up with an injury that required the exact service they were trying to avoid for three times as long and at an even greater cost.

To give you an idea of what the plan might include: we have identified a fitness gap of 20-metres in walking endurance.

From our baseline, we will also establish walking speed and effort. The goal of exercise prescription will be to build walking endurance sustainably (making fitness gains without excessive fatigue and minimising injury risk). For simplicity’s sake, we will have a three-week program to build the fitness required to cover 30 metres.

In week one, we will aim to reach 15 metres by the end of the week, 20 metres by the end of week two, and 30 metres by week three. A small but progressive overload from week one to three forces the body (and mind) to adapt.

As noted at the start of this article, this process can apply to most scenarios.

When you get to the planning phase, the key is a slight incremental progression over time. For 99% of people, a well-designed plan will usually take 8-10 weeks to complete. Why? Because it usually takes this amount of time for the human body to adapt and build sustainable fitness.

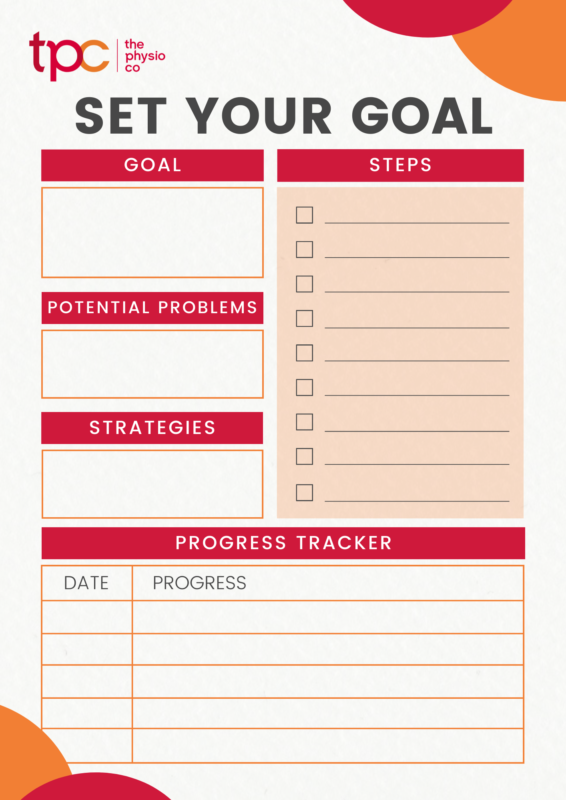

DOWNLOAD YOUR PRINTABLE GOAL PLANNER

The Physio Co’s vision is to help more seniors smash their meaningful goals. If you think we can help you, your mum or your dad get back to doing something you loved pre-pandemic, please contact our customer care team to find out how we can help.

Article written by Mike Quinn, The Physio Co.

1300 797 793

1300 797 793